Naulakhi Kothi: Ali Akbar Natiq's novel on colonial, pre-partition Punjab haunts the readers

Lamat R Hasan

NewsBits.in

New Delhi: When William returns to pre-Partition Punjab after pursuing a 'tiresome' education in England, he gets posted to Jalalabad as its assistant commissioner. The Englishman is not happy with his posting, as Jalalabad is far away from 'Naulakhi Kothi', his ancestral home near Okara, built by his gallant ancestors who made Hindustan their home 150 years ago.

William missed Naulakhi Kothi in the eight years he had been away, and memories of a childhood well spent in this grand red-brick kothi had kept him warm in the cold and colourless climes of England.

William is eager to change Hindustan’s landscape, especially Punjab’s. He wants to build British schools for the locals and change the course of their destiny. His family sees him as more loyal to the locals than to the British government. His seniors in the civil service are aware of William’s love for everything “local”. Hailey, the senior officer he reports to, tells him “we are here to rule these lands, not romance them”.

William does his best to maintain a distance between the “ruler and the ruled”, though he is angry at being posted to Jalalabad, angry at the Indian babus who often read from over their spectacles rather than through them, and angry at all Hindustanis who stare at him as if he were an artifact in a museum.

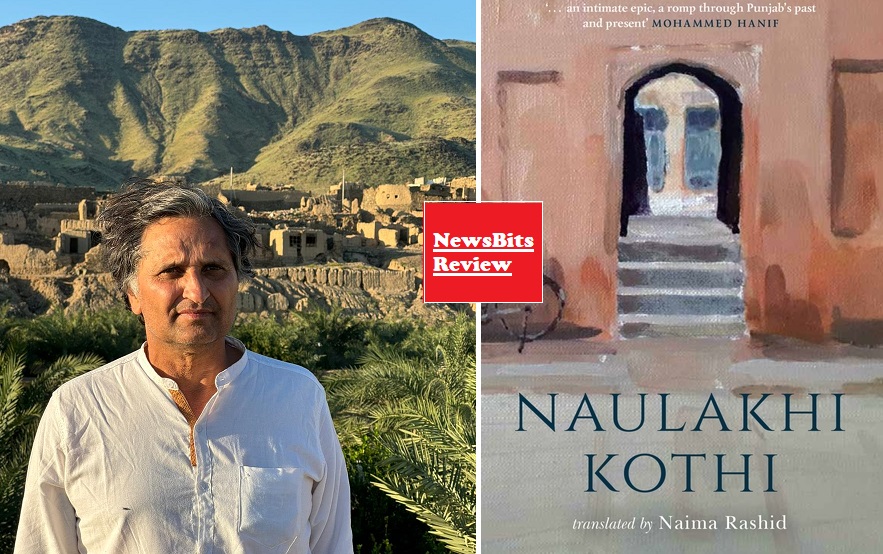

“Naulakhi Kothi” elegantly absorbs the sights and sounds of pre-Partition rural Punjab and overwhelms with its plethora of characters and the complex rivalries of the landed gentry of that era. The story by Ali Akbar Natiq - who is considered the doyen of modern Urdu literature - begins in the years leading up to the Partition of India and goes on till the late 1980s, along the way exploring inherent human

emotions and how destiny can trample the best laid plans. Natiq’s compassionate and compelling portrayal of an outsider becoming a victim of unforeseen circumstance is heart-wrenching.

When William arrives in Jalalabad – where Punjabi Muslim and Sikh rivalry is inter-generational - he observes its state of neglect. The region is barren and the few trees that he spots are so far part, as if they were "not on speaking terms with each other”. Jalalabad is on fire following the death of influential Muslim landlord Sher Haider.

When his inexperienced son, the rather suave Ghulam Haider, who has been deliberately kept away from Jalalabad – first in London and then in Lahore - returns home, he barely gets time to mourn his father’s death. He is devastated by the attacks on his men and land by the Sikhs.

He visits the assistant commissioner’s office in Jalalabad to lodge a formal complaint. William, who is getting used to meeting Hindustanis with unkempt looks and a flair for flattery, is pleasantly surprised to meet the well-spoken and well-dressed Ghulam Haider.

William takes an active interest in resolving the Muslim-Sikh rivalry. However, his plans are grounded as he faces resistance at both the junior and senior levels.

He visits the Sikh leader, Saudha Singh, the arch-enemy of the Haiders, who treats William like “a white schoolboy”. William lets him know that Singh cannot have a free run in this territory. “At least, this much is clear that Ranjit Singh is no longer the ruler of Punjab. We are,” William unleashes his tough self on Singh.

Muslims see the turn of events favouring Ghulam Haider, and some attribute his impending victory to his “affair with the viceroy’s daughter.” When the braggart, who spread this rumour, is taken to task by a senior member of the Muslim community, he claims he had heard it on the “All India Radio”, “…Chacha Feeqay, there is a magic box …Inside that box is a djinn who can predict the future...”

William changes the landscape of Jalalabad in the four years he is there. He is posted out to another town, but deliberately not to Okra where his heart is. His new accommodation is even more palatial and impressive, but not as grand as Naulakhi Kothi, which his grandfather had built. He thinks to himself that the British are seeking revenge for the narrow spaces of England by making opulent kothis in Hindustan, and living the life of nawabs.

He marries Cathy, whom he met in England and who is eager to move to Hindustan and become a memsahib. Natiq, who wrote “Naulakhi Kothi” in Urdu nearly a decade ago, is at his absolute best when he probes the minds of both British and Hindustanis.

“For Cathy, marrying William was no less than marrying a prince...Young girls in England remained on the lookout for a boy who had done his Indian Civil Service. Once they got hold of such a boy, they were set for life,” he writes. Within a few years of service, William realises he is a “puppet” in the hands of the empire, that “British officers treated their subjects like women”, and that his own wife was turning against him for favouring the locals.

As the momentum to free India from the British gathers steam, William, whose career in the civil service has only started, is consumed by the turn of events. He cannot understand “the rising nonsense of freedom” or why the other British civil servants were heading back to England. He can’t imagine being kicked out of Hindustan, as he was born in this land, and was the true son of the soil.

Translator Naima Rashid successfully retains the flavour of Natiq’s world – “its texture, colour and personality” - as she points out in her introductory note. It is easy to be transported to that fascinating era when you hear a Punjabi character call out, “O Karamatay” or “O Feeqay”.

Since Rashid’s translation is excellent, the few editorial flaws that have crept in are rather annoying. The text is repetitive at times, there are errors in names (Dalbeer Ali vs Dalbeer Singh), and in one important chapter when William unites with his family and friends, the sequence of events is absurd.

Throughout the novel the Islamic prayer times are employed to convey the sense of time by the locals. However, it sounds odd when William tells his juniors: “Let us reach Jalalabad by Asar (evening prayer) today…” or when he says “God Willing” (InshAllah).

Natiq is the author of 15 books, across the genres of fiction, poetry, biography and literary criticism. His work has been translated into English, Hindi and German. Rashid is an author, poet, and translator. She has translated three works from Urdu and French into English, and her own fiction and poetry are forthcoming 2024 onward.

The unknown narrator of the story is a school boy who accidentally meets William on a May morning while bunking school. He strikes an unlikely friendship with William, and learns everything about him over a span of a few years. It hits hard when William tells the school boy on his first meeting, “…don’t become a clerk after finishing your studies. Learn a skill instead.”

William’s story is going to haunt the readers long after the last page of this magnum opus is turned. “Naulakhi Kothi” is a highly recommended read.

Book: Naulakhi Kothi

Author: Ali Akbar Natiq

Translator: Naima Rashid

Publisher: Penguin

Pages: 462

Price: Rs 599